The crime of money laundering is a complex form of financial offense; money obtained from an illegal operation is made to appear legitimate. Hence, it gives individuals who commit the act a safe way to use that money without suspicion from law enforcement.

But what is money laundering in simple terms? It is a criminal act involving an organized system of manipulating funds through various means to evade detection by regulatory authorities.

In this guide, we’ll dive deep into what is money laundering and an example, the techniques used by criminals, and how businesses can prevent it.

What is money laundering, and why is it illegal?

Money laundering is the act of hiding illegally gained money so that it appears “clean” and is acceptable to the banking system. This occurs when the “dirty” money that was gained through illegal means (drugs, corruption, fraud, and organized crime) is changed to become “clean,” or permissible, money that can be added to the banking system without attracting attention.

Most countries recognise money laundering as a unique financial crime with legal consequences such as fines, imprisonment, and confiscation of assets. Beyond these legal penalties, money laundering undermines the integrity of the banking system and facilitates corruption, ongoing criminal activity, and even terrorism.

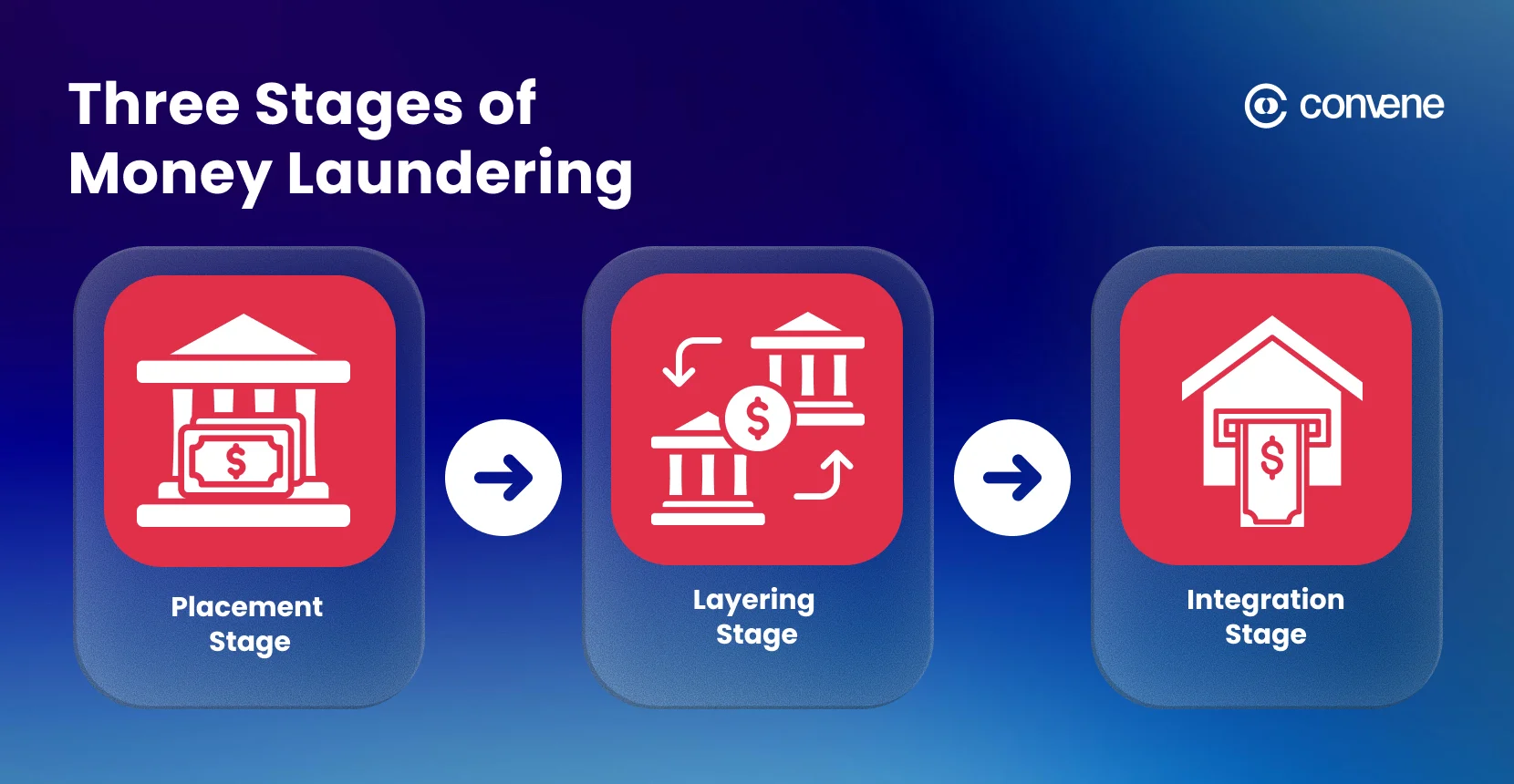

What are the key stages of money laundering?

The three stages of money laundering explained here are:

- Placement Stage: Illegitimate funds are added to the banking system in various ways, including cash deposits, cash-intensive businesses, etc.

- Layering Stage: A series of complex transactions used to confuse an auditor’s ability to track the money. Transactions such as moving funds between multiple banking accounts of various banks, moving funds between countries, or utilising shell companies to hide the actual ownership of the cash.

- Integration Stage: The money is returned to the legitimate economy through transactions such as buying real estate or receiving business income.

Although the three stages occur separately in most situations, the methods used to launder money overlap, repeat, and are modified to exploit loopholes in regulatory or technological environments.

How to know if someone is laundering money?

Money laundering detection requires the use of statistical methods to identify instances of behavior or activity with no origin to legitimate financial activity. Such methods are implemented as part of an anti-money laundering (AML) plan, which encompasses policies and controls designed to prevent, detect, and report potential money laundering.

Within an AML plan, organizations apply a range of statistical measures, including (but not limited to):

- Data mining techniques to analyze volumes of transactional or customer data and determine unusual patterns.

- Machine learning to learn from historical transaction data and distinguish normal behaviors from “potentially” illicit ones.

- Anomaly detection techniques to flag transactions that are considered outliers, such as large transfers or atypical fund movements.

- Predictive analytics using statistical models to forecast which of the future transactions are likely to be suspicious.

- Network analysis and relationship mapping to examine connections between accounts, entities, and transaction flows, as well as explore complex transaction webs.

Once an anomaly is identified, investigators must examine and determine its potential causes. The detection process is not conclusive in identifying culpability, as any red flag could have a legitimate explanation.

Learn more about how criminals do it and real-life money laundering examples in the next section.

Related Reading: [Download] AI in Financial Services: Innovation, Risk, and Governance Guide

How Does Money Laundering Work? (Techniques and Actual Examples)

Before you can create an AML plan, you must understand how this crime actually works. So how does money laundering work, and what specific techniques do criminals use? Read to know.

1. Structuring (Smurfing)

Structuring money, also called smurfing, is an approach criminals take to avoid being detected. They basically create multiple small monetary transactions to make it appear as legitimate cash negotiations. By running smaller amounts, launderers can conceal their legal proceeds as low-risk or routine transactions.

Also, with the utilization of several entities, these small transactions can be geographically dispersed, not drawing any attention or being identified as money laundering schemes. Structuring can also be done through advanced layering schemes such as the use of shell companies, offshore accounts, or third-party intermediaries — further distancing illicit funds from their original source.

Actual Case of Structuring Money:

In Australia, a woman was sentenced in 2025 for her role in a sophisticated $3.8 million money laundering syndicate where she acted as a money mule. She utilized numerous bank accounts and physical disguises to deposit illicit funds below reporting thresholds across multiple ATMs before transferring proceeds overseas.

2. Layering via Complex Financial Transfers

The technique used to create a layer of concealment between dirty money and its source is called layering. Some methods of layering include:

- shuffling money through multiple wire transfers,

- moving it between a series of shell companies,

- overseas locations using banking jurisdictions that prohibit access to your financial data,

- changing assets from cash to crypto assets or luxury items, and

- using life insurance policies as a source of cash out.

By not keeping the money in one place, the audit trail is disrupted, and connecting the final “clean” funds to their original source becomes extremely difficult for investigators.

Actual Case of Layering:

In June 2025, the Enforcement Directorate (ED) in India conducted searches at multiple locations to investigate an ongoing money laundering involving the Foreign Exchange Trading Platform OctaFx. The investigation found that OctaFx had unlawfully taken about $89 million from Indian investors, operated without permission from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), and funneled the funds through a massive web of front companies and false e-commerce sites.

3. Trade-Based Money Laundering (TBML)

Criminals engage in trade-based money laundering (TBML) by making unlawful financial activity appear to be part of a legitimate international trade transaction. They do it through asset-multiplying exchanges with global traders, or by engaging in corrupt activities (bribes) within customs to avoid established channels.

Criminals use international trade to transfer illegal funds across international borders since TBML does not require the physical movement of cash across a border.

Below are the usual techniques used by criminals to commit TBML:

- Over-invoicing: Criminal exporter bills goods for a higher amount (than their actual price) and receives the excess as “legitimate payment.”

- Under-invoicing: The importer understates the value to transfer the excess offshore undetected.

- Phantom shipments: Goods are never shipped, but invoices are used to justify fund movement.

Actual Case of Trade-Based Money Laundering:

In July 2025, Singapore’s central bank penalized nine financial firms, including Citibank, Julius Baer, and UBS, totaling $21.5 million, in connection with the 2023 money laundering case involving $2.2 billion in illicit assets. Money was gained from overseas scams and online gambling operations in Singaporean bank accounts.

4. Shell Companies and Trusts

Shell companies and trusts are legitimate organizations, but can be exploited by criminals to hide who owns and controls them and masquerade as increased business activity. Criminals use jurisdictions with poor transparency laws to create shell companies and trusts that exist only on paper.

Criminals can transfer illicit funds using these organizations and hide their funds as company income, corporate loans, or payments for services. Because of the separation between legal ownership and de facto control, it is particularly difficult to hold the legal owners of shell companies and trusts accountable.

Actual Case of Laundering Through Shell Companies:

In May 2025, a “virtual CFO” business owner from Rhode Island pleaded guilty to laundering more than $35 million in proceeds from internet fraud by creating and operating multiple shell companies to receive the illicit funds and conceal their origin. The shell companies were also founded to open fraudulent business bank accounts in Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

5. Casino and Gambling Laundering

Casinos are highly vulnerable to money laundering due to the volume of cash they have on hand and the way they document winnings. Because casinos give criminals opportunities to convert their illegal funds into gambling chips or credits, they typically place low-limit bets to reduce their losses before cashing out.

Their documentation of winnings reestablishes such proceeds as “lawful” gambling income and enables criminals to deposit into banks with little to no suspicion. This is usually conducted in areas where a casino’s anti-money laundering protections are weak.

Actual Case of Casino and Gambling Laundering:

In November 2025, the U.S. Treasury sanctioned a criminal network alleged to be laundering cartel drug proceeds through Mexican casinos, freezing their U.S. assets and barring U.S. financial dealings. Hence, the Treasury is proposing stricter policies for casinos, especially on how they can be misused to launder illicit funds through gaming receipts and cross‑border movement.

6. Cryptocurrency Laundering

Many criminals and other organized crime groups today have found ways to launder illicit funds through cryptocurrency. With the rapid evolution of DeFi (decentralized finance) and cross-chain bridges, there has been a rise in criminal money laundering activities associated directly with the use of cryptocurrency. And as crypto laundering proliferates, regulators and law enforcement are facing a fast-growing problem that requires multifaceted responses, such as blockchain forensics and tighter compliance frameworks.

Actual Case of Cryptocurrency Laundering:

In November 2024, the operator of Bitcoin Fog was sentenced to about 12 years in prison after law enforcement traced over 1.2 million bitcoins processed through the darknet service, which facilitated laundering of funds from drug sales and cybercrime.

Note: A single red flag is not evidence of money laundering and requires further investigation and increased scrutiny. Evidence supporting criminal action can only be provided by law enforcement and/or regulatory agencies.

How to Prevent Money Laundering: Key Areas in AML Programs

In order to prevent money laundering, a simple internal oversight is not going to be enough. It is ideal that your anti-money laundering program touches on critical aspects like:

1. Regulatory and Policy Frameworks

An AML program’s foundation should be in compliance with applicable international and local laws and regulations. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendations serve as the global baseline of expected activities for AML programs, including:

- Customer Due Diligence (CDD)

- Ongoing monitoring

- Record retention

- Suspicious activity identification and reporting

- Risk-based internal controls

Such standards must be reflected in company policies and enforced through documented procedures and escalation paths.

Under the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), financial institutions in the U.S. are required to maintain detailed records and report all cash transactions of more than $10,000, and to notify law enforcement of suspected criminal activity through the filing of Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs).

2. Strong Customer Due Diligence and Identity Verification

Next, you need to know who you’re dealing with, and you do so through Know Your Customer (KYC) and Customer Due Diligence (CDD). They act as the first real barrier to money laundering, starting at onboarding and continuing throughout the customer relationship. Identity checks aren’t a one-time exercise; they evolve over time.

KYC also goes beyond simply confirming a name and an ID. It includes identifying beneficial owners or the real people who ultimately control or profit from an account. These individuals must be clearly identified and verified, not assumed.

On top of that, customers must be screened against global sanctions lists and politically exposed persons (PEPs). This process is typically automated, but the risk it addresses is very real.

3. Transaction Monitoring and Suspicious Activity Reporting

AML monitoring systems track all incoming and outgoing transactions. Many systems have behaviour-based and anomaly-based capabilities that examine customer transaction history and behaviour to detect evidence of money laundering. In other words, they can flag customers whose transaction activity deviates from established patterns as suspicious or must investigate further.

Moreover, such systems can generate Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) for financial institutions, law enforcement, and financial investigation units (FIUs). This way, companies can determine whether to investigate, seize those assets, or take legal action against the people involved in the schemes.

4. Internal Governance, Training, and Independent Review

An AML program must have an internal governance structure in addition to technology. Financial institutions should have documented AML policies based on a risk assessment, as well as independent compliance officers who report directly to the board of directors.

Companies must also conduct regular audits to determine if the institution has followed the established model, identify and report on potential issues, and assess operational processes. Employee training should be extensive, tackling each person’s job and responsibilities, applicable anti-money laundering typologies (e.g., SAR/STR Protocols), and reportable case studies.

5. Advanced AI and Risk-Based Automation

Traditional AML systems now prove to be insufficient to handle increasing transaction volumes, real-time payments, and cross-border activities. Many modern businesses today switch to advanced analytics and artificial intelligence (AI) and integrate them into their AML processes. AI-driven AML systems can effectively:

- detect complex, non-linear laundering patterns,

- identify hidden relationships between accounts or transactions,

- reduce false positives, and

- adapt to emerging laundering typologies like mule networks.

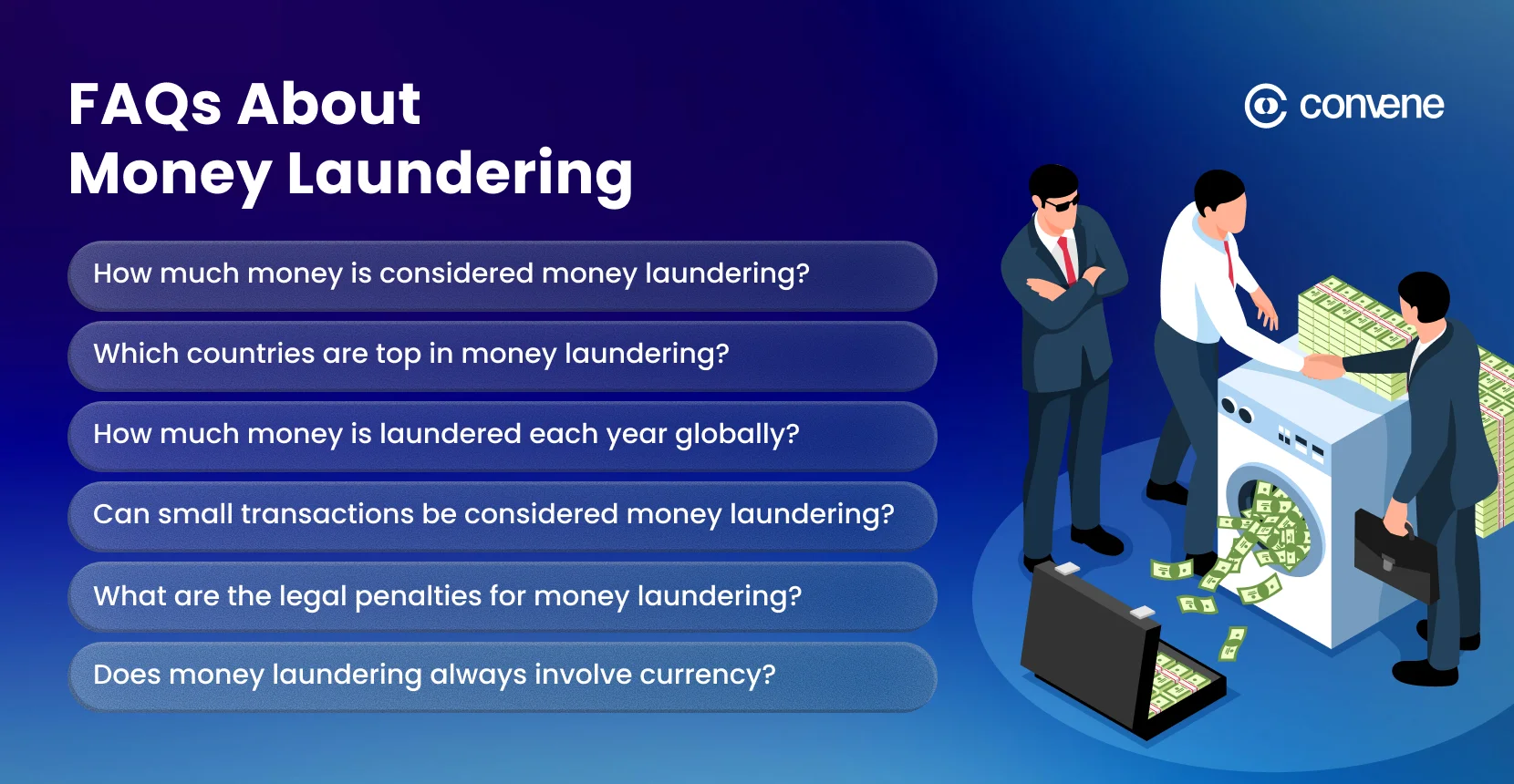

Frequently Asked Questions About Money Laundering

How much money is considered money laundering?

There’s no standard for how much money qualifies as money laundering. Instead, anti-money laundering (AML) laws criminalize disguising illicit funds, regardless of amount, and many laws specify minimum transaction amounts for presumptive offenses.

For instance, in the United States, federal law under 18 U.S.C. § 1957 makes it a crime knowingly to engage in a financial transaction involving criminally derived property of more than $10,000 with the intent to promote unlawful activity. Other jurisdictions vary. Some define laundering offenses by transaction patterns, frequency of activity, or intent to conceal the source, rather than a fixed sum.

Which countries are top in money laundering?

Top jurisdictions for money laundering can be considered in two ways: where illicit flows originate and where weak controls make laundering more feasible.

Based on the Basel AML Index, which measures a country’s overall risk of money laundering and terrorist financing, these countries consistently rank among the highest-risk jurisdictions: Myanmar, Haiti, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, and Venezuela.

These jurisdictions also appear repeatedly in global AML risk assessments and in international bodies’ enforcement lists (FATF and EU risk lists).

How much money is laundered each year globally?

Estimates on laundered money globally and annually may vary. However, some independent studies suggest that between $800 billion and $2 trillion annually is laundered worldwide, amounting to roughly 2–5 % of global GDP. Only a small fraction of these flows are eventually detected and seized, underscoring the scale of the challenge for enforcement and AML compliance.

Can small transactions be considered money laundering?

Yes. Small transactions can be treated as money laundering under AML laws. For instance, some criminals would break large sums into smaller ones (structuring or smurfing) to avoid reporting limits/breaks. This is a common tactic that compliance systems are designed to detect.

What are the legal penalties for money laundering?

Most jurisdictions establish penalties for money laundering based on the size of the transaction. Criminal convictions for those who manage the laundering process would generally have multi-year sentences, and both the criminals and corporations would be subject to fines and asset forfeiture. Additionally, if a financial institution does not have adequate AML controls in place, it could face regulatory sanctions and potentially large penalties.

Does money laundering always involve currency?

No. Money laundering does not always involve physical currency. In fact, modern schemes today frequently use non-cash instruments or digital systems to obscure the original source of illicit funds. Some non-cash forms include electronic or wire transfers, digital assets or cryptocurrencies, and high-value assets like luxury items (e.g. art, jewelry, vehicles).

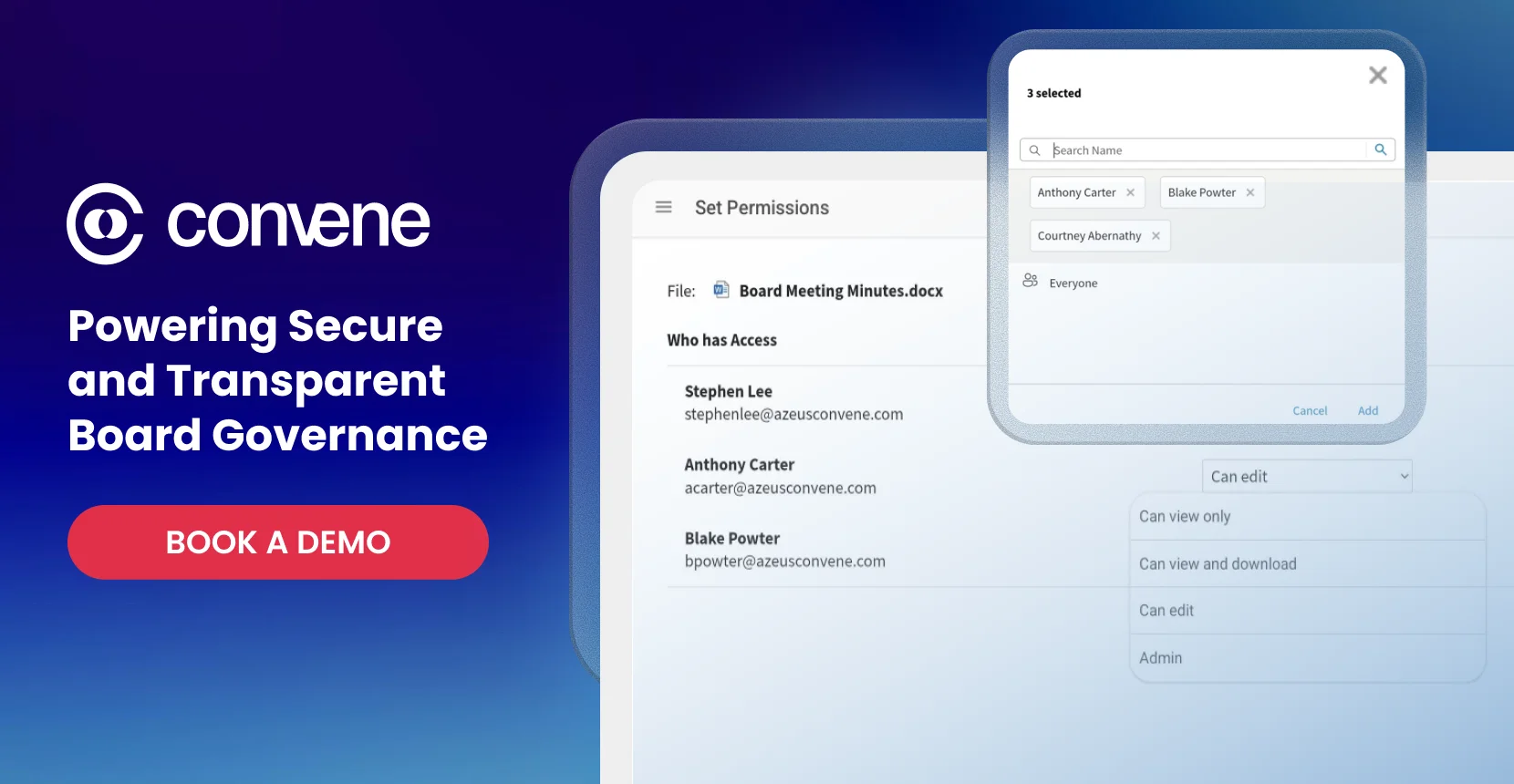

Convene Board Portal: Powering Secure and Transparent Board Governance

Convene, a globally leading board portal, is designed with enterprise-level security and document management features for effective anti-money laundering programs. Our platform empowers boards worldwide to oversee AML with confidence — and most importantly, with the best tools. Convene gives you the powerful features you need for your AML plan:

- Controlled Access and Data Protection: The use of Multi-Level User Access, AES-256 Encryption for data at rest, 2048-Bit TLS/RSA for data in transit, and restrictions on copying means compliance reports are locked down and accessible only to authorized users.

- High-Standard System Security: Convene’s Role-Based Access Control (RBAC), Audit Trails, and per-user login logs ensure that every action taken on the platform is recorded and every decision is traceable. The regulators will not just see that you’re compliant but also have proof of that compliance.

- Centralized Document Hub: All AML-related documents (monitoring reports, risk scorecards, audit files, governance documents) are housed in a secure, fully-searchable library. Documents are also protected with flexible watermarks to prevent information leaks.

- Faster Risk Decisions and Regulatory Sign-Off: Transform your slow-moving email threads into quick board actions. Formalize AML policy changes, high-risk approvals, or compliance strategy shifts with Convene’s Resolutions, Weighted Voting, and integrated e-Signatures (Adobe Sign, DocuSign, WeeTrust).

With Convene, AML oversight stops being a scramble and starts being secure, streamlined, and regulator-ready. Request a demo now.

Jielynne is a Content Marketing Writer at Convene. With over six years of professional writing experience, she has worked with several SEO and digital marketing agencies, both local and international. She strives in crafting clear marketing copies and creative content for various platforms of Convene, such as the website and social media. Jielynne displays a decided lack of knowledge about football and calculus, but proudly aces in literary arts and corporate governance.