In corporate governance, power dynamics often shape every decision. The Chatham House Rule serves as the secret sauce for candid yet discreet conversations in Australian boardrooms. This rule—allowing participants to speak freely while keeping identities under wraps—creates a careful balance between transparency and confidentiality.

As boardrooms go digital, board management software has become a natural ally in reinforcing the needed discretion in the Rule. Access-controlled document sharing and secure meeting workflows are just a few features that can protect confidentiality while fostering open dialogue.

Learn about the Chatham House Rule meaning, its benefits, and how Convene board management software can help you effectively adopt the Rule in your meetings.

What is the Chatham House Rule?

The Chatham House Rule, also known as Chatham House, is a communication framework designed to encourage openness and free exchange of ideas in meetings. It takes its name from Chatham House, the London headquarters of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, where the Rule was created in 1927. The Rule is employed in diplomatic discussions, corporate strategy sessions, academic roundtables, off-the-record media briefings, and even think tank events.

The Rule reads:

“When a meeting, or part thereof, is held under the Chatham House Rule, participants are free to use the information received, but neither the identity nor the affiliation of the speaker(s), nor that of any other participant, may be revealed.”

Moreover, the Rule is proven beneficial for facilitating discussions that demand confidential consultation, mutual trust, and risk-free expression of ideas. Hence, making it a globally respected tool for enabling honest, safe, and impactful dialogue.

What are the benefits of the Chatham House Rule?

When open dialogue is essential but anonymity encourages honesty, the Chatham House Rule Australia offers a powerful solution. Listed are ten benefits the Rule brings to boardroom discussions and decision-making.

1. Balancing openness and confidentiality

One benefit of the Chatham House Rule is that it can cut through surface-level diplomacy, which gives directors a rare licence to speak openly. Such kind of environment enables board members to willingly raise difficult truths or voice dissent. Doing so enables what leadership teams often lack: genuine candour. That openness may spark uncomfortable yet necessary dialogue, which is far more productive than performative agreement.

At the same time, the Rule shields identities and not ideas. Directors can share deep, situational talks without being directly quoted, which then allows the group to synthesise takeaways without risking their reputation. In other words, it makes the conversation safe, but not sterile.

2. Protects whistleblowers and dissenting insiders

Regardless of how ethical a company is, its board is not guaranteed to be psychologically safe. Junior directors, whistleblowers, or tenured members may still hesitate to call out misconduct. Some often fear the backlash they can get from senior leadership or shareholders. The Chatham House Rule acts as a protective buffer for people to challenge decisions without exposing themselves to backlash.

Think of a board member who uncovers troubling discrepancies in a supplier contract during an audit review. Under the Rule, they can voice their concerns without being singled out.

3. Supports constructive engagement among opposing sides

In most cases, boards are split across ideologies, generations, or geographies, even often leading to factions. This is where the Chatham House Rule Australia plays a part: by taking ego off the table and encouraging resolutions. It is not “my position vs. yours” but “how do we solve this?”

For instance, a board split over divesting a profitable but environmentally harmful product line. With the Rule, each can express their concerns (e.g., financial, moral) without fear of such views being used against them. The result? Honest debate.

At the same time, the Rule provides space for creative thinking and unconventional strategies, without risk of premature judgement. Directors can freely pitch, challenge norms, or test and improve risky proposals.

4. Creates space for admission of institutional failures

Accountability doesn’t always require exposure. Sometimes, board members are more honest about mistakes when they’re not under intense scrutiny. The Chatham House Rule creates a space where directors can examine those missteps (e.g., cultural misfires, compliance lapses) without posturing or defensiveness.

For instance, the board held a private debrief following a failed product launch, losing millions. Under the Rule, there are no blame games; directors can openly question whether their own overconfidence or flawed assumptions caused the problem.

5. Reduces chilling effect in high-risk environments

In entities exposed to volatile markets or geopolitical risk, speaking freely might come with real consequences. Board members frequently exercise self-censorship to steer clear of potential diplomatic pitfalls, such as managing state-owned partnerships. Fortunately, the Chatham House Rule allows for a comprehensive approach.

For example, in a firm operating in a jurisdiction with a fragile rule of law and political surveillance, a director may want to quietly scale back operations to avoid entanglement. Voicing that, however, could be seen as unpatriotic or defeatist. Under the Rule, this can be aired, evaluated, and debated without fear of internal leaks or external provocation.

6. Reduces the risk of public misrepresentation

A single quote from a boardroom—misheard, clipped, or taken out of context—can spiral into a media storm. In high-profile companies, this risk isn’t hypothetical; it’s operational. The Chatham House Rule acts as a firewall against that distortion, allowing board members to speak with nuance, even on controversial issues.

Suppose a director questions whether the company is “overcommitting to ESG targets” amid a market downturn. If taken out of context, that statement could significantly tank the firm’s sustainability ratings. But within the confines of a Chatham House discussion, it’s recognised for what it is: a call to balance ambition with feasibility. Honest scrutiny can happen without fueling the rumour mill.

7. Enhances professional development and learning

Not every board member is an expert in every domain. The best directors are lifelong learners, but that’s hard to admit when everyone else in the room is a former CEO or CFO. The Chatham House Rule flattens the power gradient, creating a learning space where vulnerability isn’t punished but welcomed.

For instance, during a board induction programme, a new director unfamiliar with climate reporting might hesitate to ask “basic” questions. Under the Rule, they can speak up, gaining clarity and context without judgement. Veteran directors, in turn, often share hard-won lessons or personal failures—contributions that deepen trust and accelerate group development.

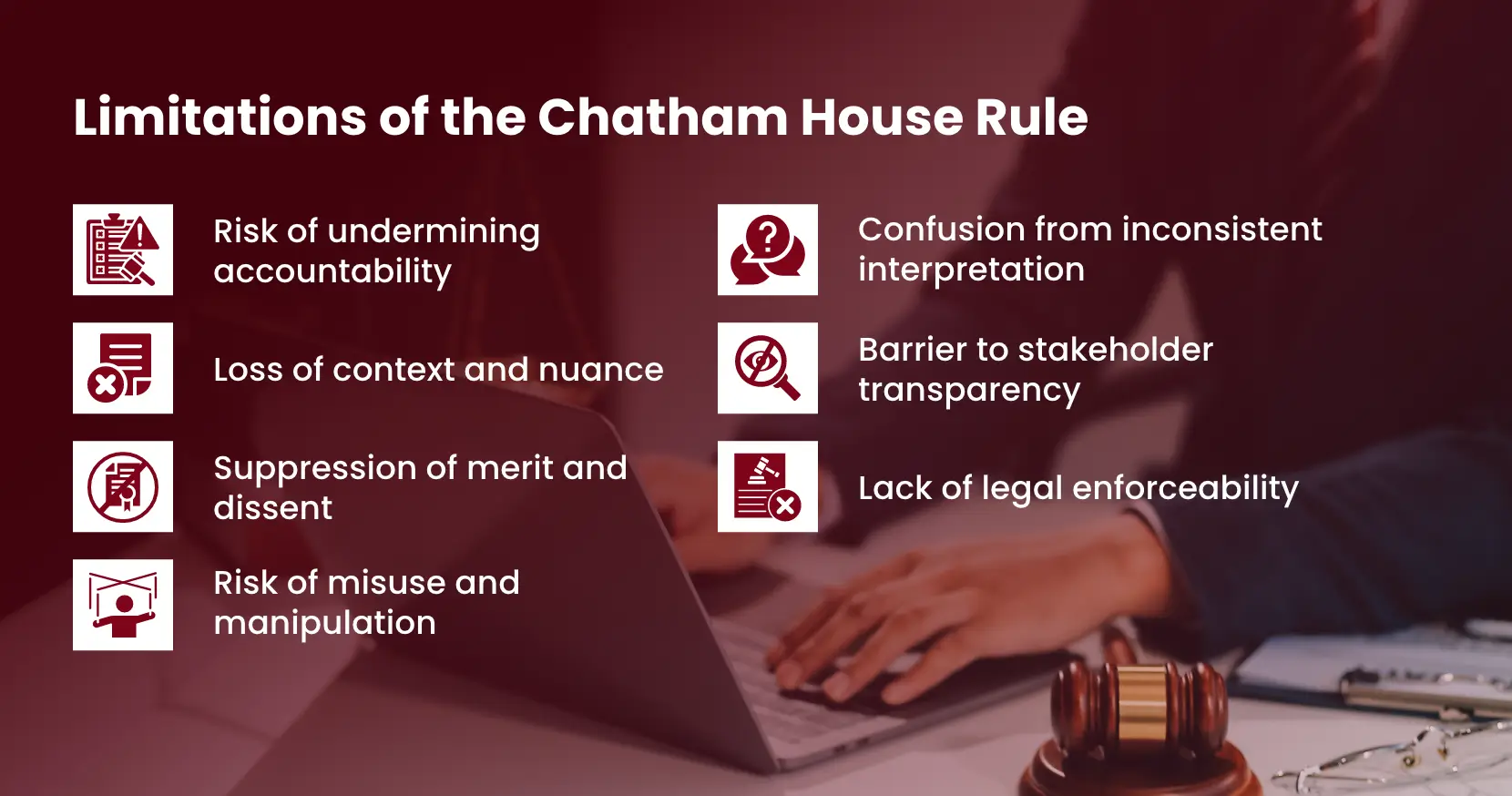

Limitations of the Chatham House Rule

While the Chatham House Rule is used for encouraging open dialogue, it also comes with some limitations. Anonymity can enable honesty, but can also blur accountability or suppress valuable dissent. Understanding such limitations is key to applying the Rule with intention.

1. Risk of undermining accountability

While the Chatham House Rule encourages openness, its veil of anonymity may erode accountability when bold claims go unattributed. Boards can even lose a clear trail of thought without knowing who voiced critical opposition. They may also find themselves unable to explain or justify their rationale due to anonymity blurring the record. Such is likely to happen in face of scrutiny, like defending a controversial compensation scheme to shareholders.

2. Loss of context and nuance

Stripped of speaker identity and intent, statements lose context. In a boardroom, similar comments carry different weight depending on whether they’re from a junior or senior member. Under the Chatham House Rule Australia, such nuance disappears. Hence, increasing the risk that remarks are misread, reframed, or distorted in summaries. One could mistake a casual comment about market changes for a consensus shift, thereby confusing internal plans.

3. Suppression of merit and dissent

The Chatham House Rule can flatten hierarchy, but so is merit. The worst case? Visionary ideas or hard-won insights can vanish into anonymity, receiving no acknowledgement. Although the Rule encourages open dialogue, it can unintentionally silence minority voices or newer members. For instance, a dissenting view on sustainability from a junior director may go unacknowledged. Not because it lacked merit, but because no one was aware of its source. This can result in a false appearance of consensus, wherein critical dissent is overlooked or lost entirely.

4. Risk of misuse and manipulation

The Chatham House Rule relies on discretion, creating a gap for exploitation. Protected by anonymity, malicious individuals can minimise risks, suppress opposition, or manipulate stories without worrying about being revealed. For example, a director evaluating a compliance violation may downplay warning signs that fend off further investigation. If the issue later escalates, the Rule hinders accountability: acting not as a safeguard but as a facade.

5. Confusion from inconsistent interpretation

In certain situations, the Chatham House Rule falls victim to misinterpretation. Some may treat it as a strict confidentiality mandate, while others use it to circulate anonymized content freely. Discrepancy can turn problematic in multinational or cross-industry boards, leading to confusion or inconsistent application. Without standardised onboarding processes, the Rule tends to create ambiguity and unintentional infractions.

6. Barrier to stakeholder transparency

Boards must often justify their decisions to stakeholders (e.g., investors, regulators, employees, the public). If such decisions are made under the Chatham House Rule, explaining the process behind them can be tough. Stakeholders looking for reassurance that decisions were properly debated may find only vague summaries. This proves that while the Rule protects internal candour, it can also feed perceptions of secrecy. Hence, making it hard for boards to prove that decisions were carefully debated and fair.

7. Lack of legal enforceability

The Chatham House Rule is built on trust, not law. This means it carries no legal weight and is not enforceable unless backed by NDAs or confidentiality clauses. In case sensitive information leaks under the Rule, the board has limited options for recourse. So, in high-stakes or high-risk scenarios, the Rule cannot provide legal protection.

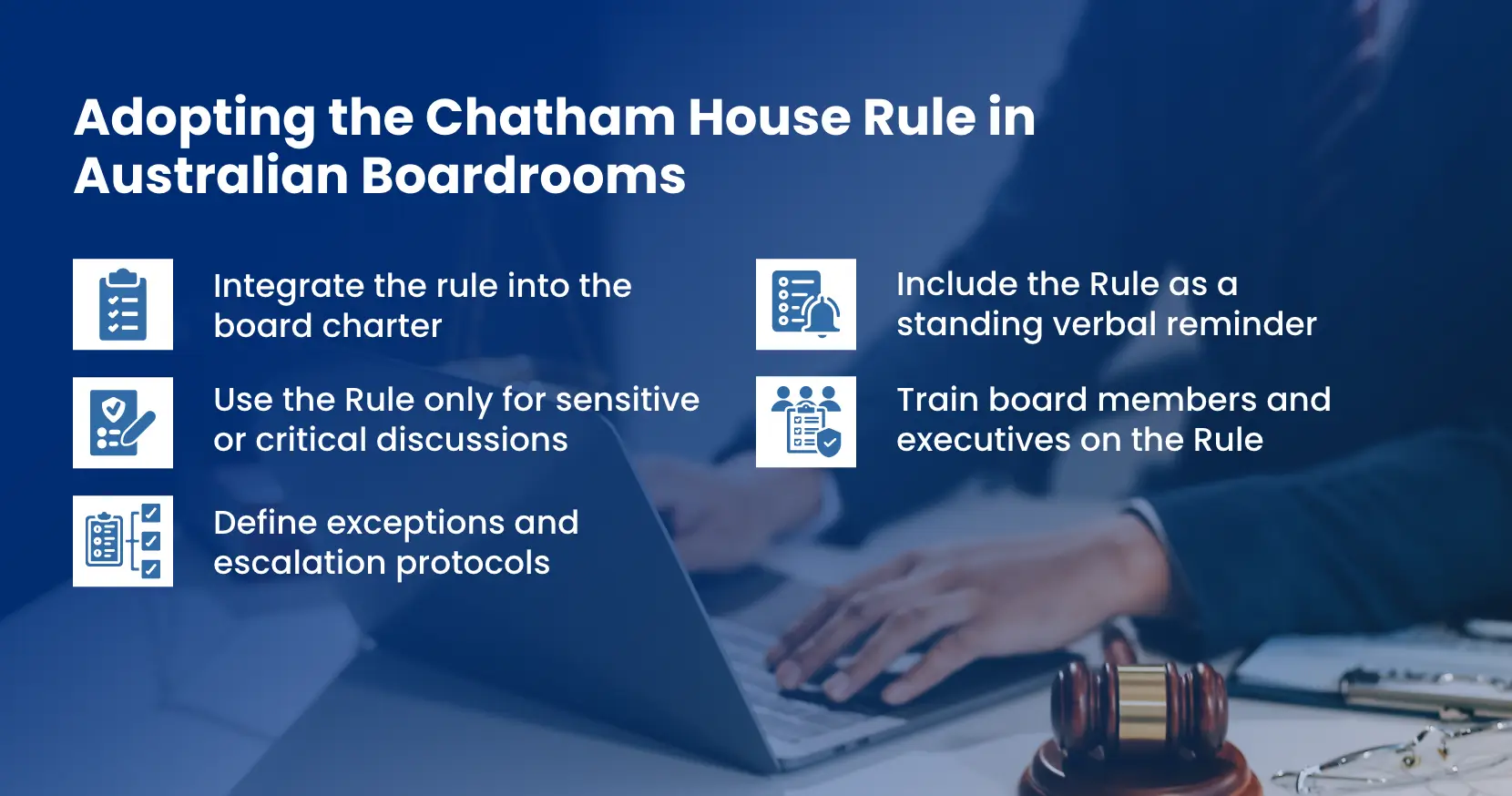

Adopting the Chatham House Rule in Australian Boardrooms

Adopting the Chatham House Rule in boardrooms is less about cloak-and-dagger confidentiality. It is more about creating a psychologically safe space for board members and executives to speak freely. Australian boards, which constantly face liability pressures and stakeholder expectations, understand the importance of applying the Rule in their discussions. But how can Australian boards adopt the Rule effectively?

1. Integrate the rule into the board charter

First thing you can do is to formally adopt the Chatham House Rule in your board’s charter. You can amend your charter to include the Rule under a section like Confidentiality and Communication. It is also ideal to reference the ASX Corporate Governance Principles (e.g., Principle 3: Instill a culture of acting lawfully, ethically, and responsibly), as a supporting basis for adopting the Rule. In the board charter clause, you can state:

“In accordance with the Chatham House Rule, board members may discuss the content of deliberations externally, provided no individuals or affiliations are identified, unless formally authorised.”

2. Use the Rule only for sensitive or critical discussions

Keep in mind that the Chatham House Rule shouldn’t be applied to all board items. Instead, use it for agenda items involving sensitive matters such as strategic shifts, high-stakes scenarios, M&A activities, or whistleblower issues. Then, label these items with a marker (e.g., “CHR”) in board packs for clarity. For instance:

CHR Agenda Item: “Preliminary merger talks with unnamed industry partner — under Chatham House Rule.”

3. Define exceptions and escalation protocols

Next, determine when the Rule does not apply. Ensure to articulate in your board policy when legal obligations (e.g., directors’ duties under the Corporations Act 2001) override the Rule. For one, you can add an exception selection in the policy clarifying:

- Where legal obligations take precedence (e.g., whistleblowing to ASIC under RG 270)

- When the board collectively votes to lift the Rule

Simultaneously, include a process for escalation to the Risk & Compliance Committee in case breaches are suspected. Consider escalation triggers such as whistleblower reports or regulator inquiries.

4. Train board members and executives on the Rule

For the Rule to be perfectly implemented, it’s best to educate board members and executives about its implications, limits, and appropriate use cases. You can do this via refresher training or annual governance sessions. However, training must clarify what the Rule does not protect. For instance, it does not override legal obligations under ASIC reporting requirements or the Corporations Act 2001.

5. Include the Rule as a standing verbal reminder

In your board discussions, the Chair should verbally invoke the Rule when relevant. Consider using chairperson scripts to set a clear reminder at the start of a session. A sample script would be:

“This agenda item is subject to the Chatham House Rule. You’re free to discuss the insights gained, but identities and affiliations must not be disclosed outside this room.”

If an external guest is invited, the Chair must confirm that the Rule also applies to them and obtain verbal acknowledgement on record.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Chatham House Rule

1. What does it mean to waive the Chatham House Rule?

Waiving the Chatham House Rule means participants agree that comments made during a meeting can be attributed to individuals (an “identity”) or publicly shared. This eliminates the confidentiality protections that the Rule normally provides.

2. What is the difference between the Chatham House Rule and the Vegas rule?

The Chatham House Rule enables ideas and insights to be shared outside the room but without identifying who said them. The Vegas Rule, on the other hand, dictates that nothing discussed in the meeting must be shared outside of it. Deemed as stricter than Chatham House, this Rule implies total confidentiality: “What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas”.

3. Is the Chatham House Rule legally binding?

No, the Chatham House Rule is not legally binding. The Rule is a convention or agreement, and not a law, so its effectiveness relies on the mutual trust and professionalism of those involved.

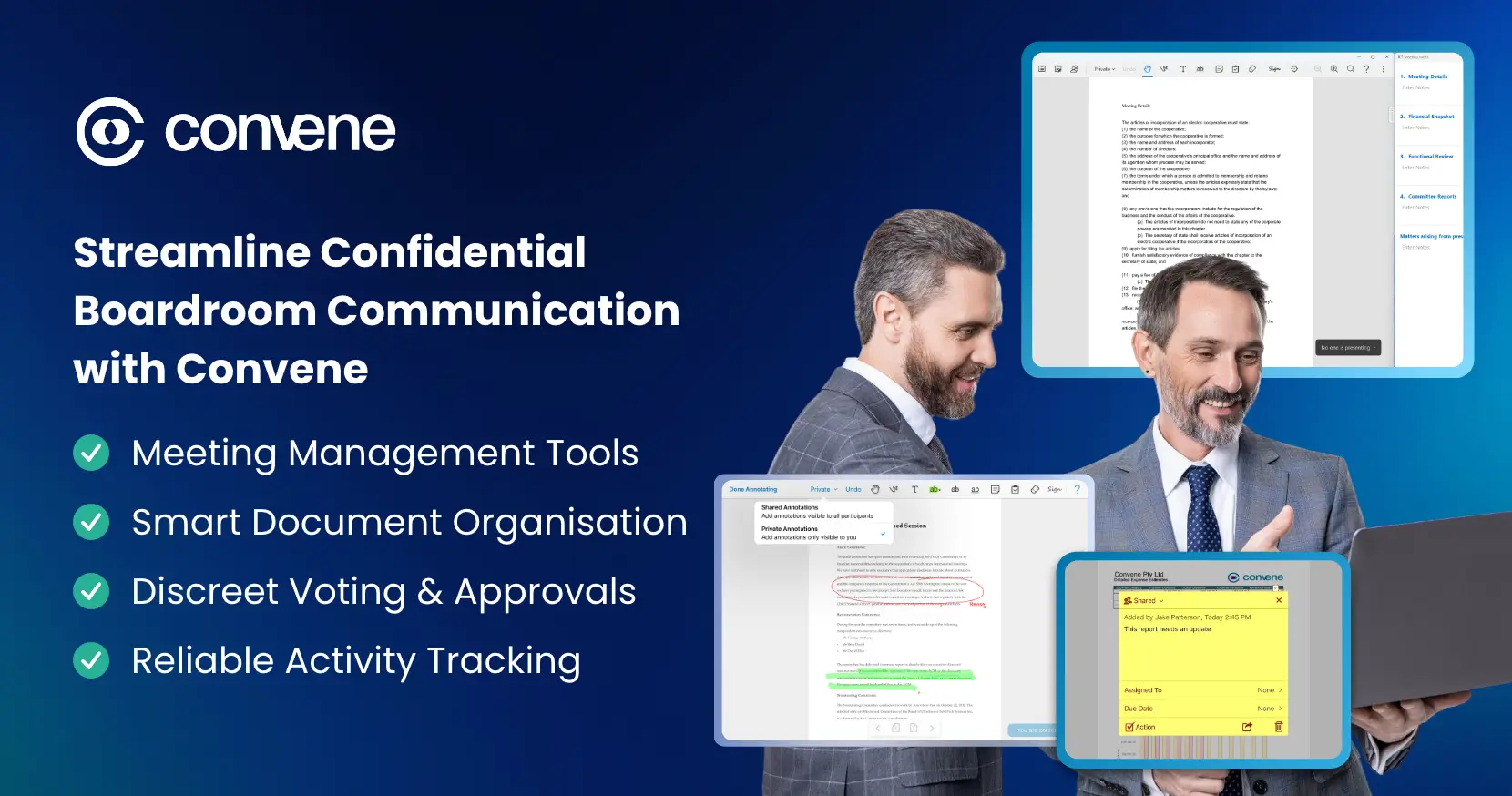

Streamline Confidential Boardroom Communication with Convene

Creating a space where directors feel safe to speak candidly is a crucial task for Australian boards. With the Chatham House, boards can foster open, honest dialogue by allowing ideas to be shared freely without attaching them to individual identities. To support such culture of secure openness, many Australian boards are opting to use board portals.

Creating a space where directors feel safe to speak candidly is a crucial task for Australian boards. With the Chatham House, boards can foster open, honest dialogue by allowing ideas to be shared freely without attaching them to individual identities. To support such culture of secure openness, many Australian boards are opting to use board portals.

Convene, one of today’s leading board software, is designed with control and confidentiality at its core. It offers a suite of features that allows Australian boards to collaborate more confidently, securely, and efficiently—ensuring what happens in the boardroom, stays in the boardroom. How can Convene make this happen?

- Meeting Management Tools: Run your live meetings with features like real-time annotations and live minute-taking, while ensuring insights are captured without naming contributors.

- Smart Document Organisation: Store all CHR-sensitive materials in a secure Document Library with scalable cloud storage, version control, and access restrictions. Directors can also easily access and sign documents within the Review Room.

- Discreet Voting & Approvals: Management resolutions with flexibility using a show of hands, secret ballot, or in-meeting voting, which is ideal for CHR-governed agenda items. Convene Poll is also available for custom vote options and proxy voting, all without compromising compliance.

- Reliable Activity Tracking: Convene’s built-in audit trail securely logs user activity, such as document access, edits, and decisions. This allows users to maintain confidentiality while ensuring accountability and oversight.

Learn more about Convene’s features and how it can help with your board discussions. Request a demo today!

Jielynne is a Content Marketing Writer at Convene. With over six years of professional writing experience, she has worked with several SEO and digital marketing agencies, both local and international. She strives in crafting clear marketing copies and creative content for various platforms of Convene, such as the website and social media. Jielynne displays a decided lack of knowledge about football and calculus, but proudly aces in literary arts and corporate governance.